The unlikely beginnings of a physicist

At the age of 12, Alicia Postuma—who uses the pronouns she/her and they/them—received a gift from her father that would chart the course of her life for decades to come: a book called How to Teach Quantum Physics to Your Dog by Chad Orzel. This unconventional introduction to the world of protons, neutrons, atoms, and quarks captivated Postuma’s imagination and set her on a path toward a career in physics. Today, as a PhD candidate at the University of Regina, Postuma reflects on the profound impact this book had on their early interest in science.

"I was insufferable talking about that book as a kid," says Postuma. "This talking dog asks its owner all kinds of questions about his job as a physicist. The author then comes up with great metaphors to explain quantum physics. It turns out that if a talking dog can understand these complicated underpinnings of our world, so can a 12-year-old."

Subatomic enchantment

Quantum physics is all about studying the world around us at the most fundamental level. Its allure – the departure from the predictable nature of classical physics—was irresistible to young Postuma. "I learned that in classical physics, if you throw a ball the same way, it will land in the same place—it’s predictable," she explains. "But quantum physics plays by completely different rules. It’s governed by probability, so you can do an experiment twice and get totally different results. This means that the rules we live by don’t apply on the very smallest scales—to the protons and neutrons—and that was mind-bending to me as a kid. It made me feel smart to know these things."

For Postuma, this early introduction made the enigmatic world of quantum physics understandable and fascinating. The idea that the microscopic universe operates under different principles than the macroscopic world was a revelation that fueled her curiosity and passion for science.

A spark ignited

Postuma’s early fascination with quantum physics laid a strong foundation for her academic pursuits. Her enthusiasm for the subject led her to study physics as an undergraduate student at Mount Allison University in New Brunswick, where they continued to explore what the field had to offer.

“During my undergrad, I had the chance to work with a particle accelerator, an experience that completely captivated me.”

Working in subatomic physics, with the chance to travel to particle accelerators all over the world, eventually landed Postuma at the University of Regina working with U of R professor of physics Dr. Garth Huber.

Standing out

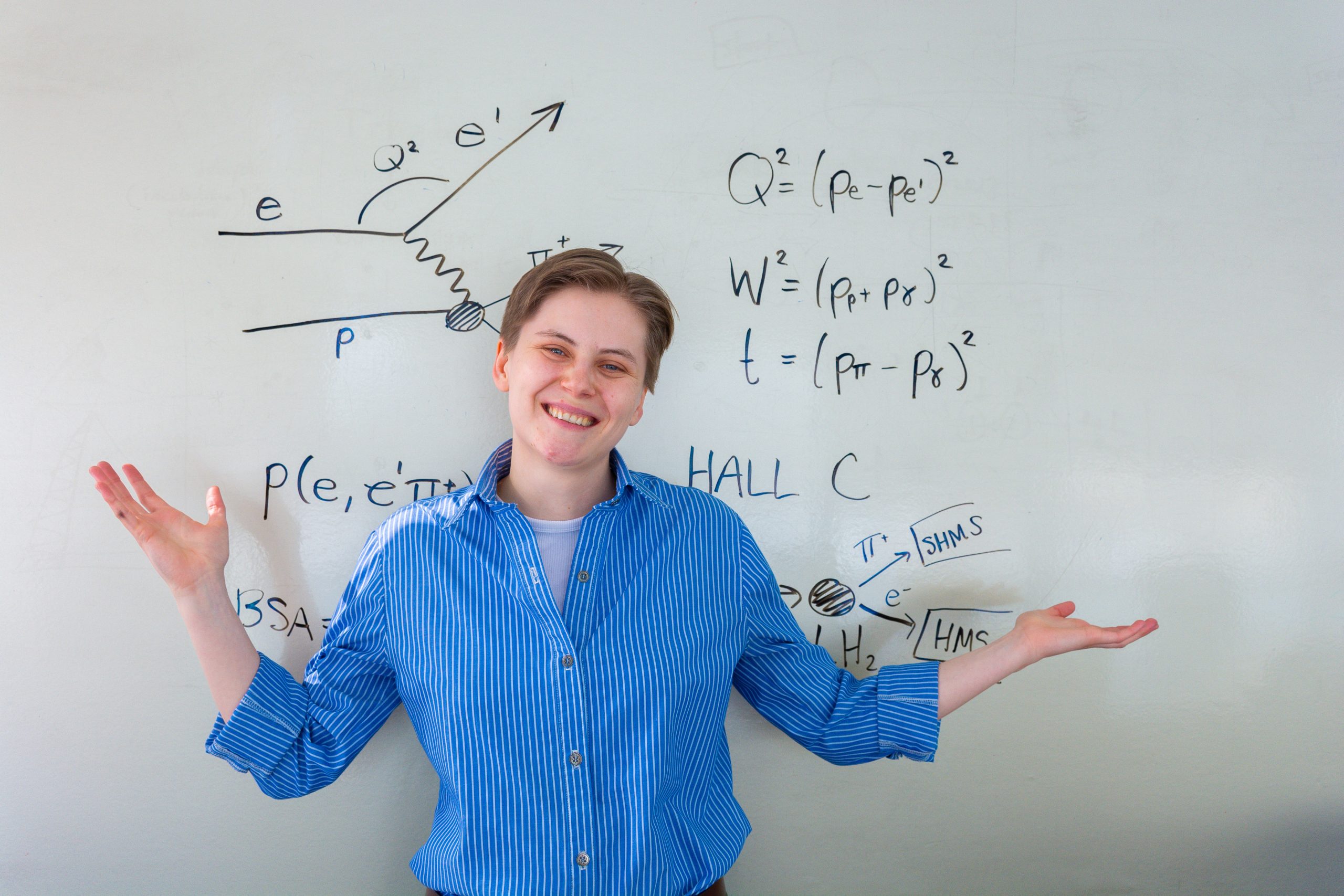

Joining one of Huber’s research programs, Postuma’s graduate work focuses on figuring out the intricacies of protons—work that takes her to the Jefferson Lab in Newport News, Virginia.

“My main goal is to better understand the interior structure of protons. There are different paths to get there, but mine is unique because I want my research to stand out,” says Postuma.

And stand out it does. Postuma recently received a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Vanier Scholarship, a prestigious award that helps Canadian institutions attract highly qualified doctoral students who demonstrate academic excellence, research potential, leadership potential, and demonstrated ability. The award is worth $50,000 a year for three years.

“Alicia is great to work with. She academically very gifted, pursues her research with passion, and is a natural leader,” says Huber, her graduate supervisor. “She did a great job mentoring our undergraduate research student last summer and has already taken major roles in organizing several national conferences held at the U o f R. Alicia is a worthy recipient of the prestigious Vanier scholarship and we are very proud of her accomplishments.”

While Postuma started at the University of Regina as a graduate student, after only a year, they fast-tracked to the PhD program. As a PhD candidate, Postuma is delving deeper into the intricacies of what makes up our world with the goal of adding to the growing body of knowledge in the field.

Exploring the quantum realm

Postuma’s research at the U of R focuses on exploring the behavior of subatomic particles and the fundamental forces that govern their interactions. Through her work, she aims to shed light on some of the most perplexing questions in physics, continuing the journey that began with a simple yet profound gift from her father.

The particles they’re working with are so small that typical experimental methods can’t be used. That’s where a particle accelerator comes in. The accelerator speeds up electrons, then, using an electron beam, smashes electrons into protons. This explodes the proton into even smaller pieces, revealing what’s inside.

“While I don’t know what will come of my work, or what technology will rely upon it in the future, I know it will be used for something that’s good for humanity. And that’s why these fundamental research programs are so important.”

“After the explosion, we look at the pieces to help determine the speed they were traveling at and the direction they were heading. We then work backwards to see how that proton would have looked before the collision.”

Postuma likens this process to throwing tennis balls at a covered sculpture and using the angles at which the balls bounce back to deduce the sculpture’s shape.

A new angle

Postuma says that most accelerator experiments knock out a small piece of the proton structure, with a small piece hurtling forward, while a bigger piece stays behind. The researchers then study the smaller piece.

“My work will look at the opposite reaction,” says Postuma. “The bigger piece will be moved forward by the accelerator, while the little piece stays behind, giving us a different angle from which to look at things. This new angle hasn't really been explored before, so we see a new part of the proton structure, giving a more complete picture overall."

Eureka!

This all sounds incredibly impressive. But why are these kinds of experiments even needed? Postuma explains with an anecdote.

A politician's inquiry into the practical applications of Michael Faraday's newly discovered "electricity" was met with Faraday's prescient yet humble response: "I do not know, but I bet that one day your government will tax it."

"So, while I don’t know what will come of my work, or what technology will rely upon it in the future, I know it will be used for something that’s good for humanity. And that’s why these fundamental research programs are so important.”

Bridging the gap

In addition to her research, Postuma is passionate about science communication. Inspired by conversations she’s had with family, friends, and students who find physics cool, but who don’t think they can do it, she is dedicated to taking complex scientific ideas and making them understandable and engaging for a broader audience.

“This work is really rewarding for me because I had no queer role models growing up. And I don’t want someone else to be in that same situation. I want there to be visibility.”

“I’m trying to shift focus outside of the university setting, because science is meant to be shared with everyone.”

By engaging with high school students and the broader community, Postuma strives to demystify quantum physics, and science in general, to inspire future scientists.

They are also working to make their field more inclusive.

“I’m working in a male-dominated field, so I work to promote science to girls. This past spring, I also chaired the 2SLBTQ+ STEM conference, an interdisciplinary conference that celebrates diversity and highlights the contributions of the 2SLBTQ+ community in science,” says Postuma. “This work is really rewarding for me because I had no queer role models growing up. And I don’t want someone else to be in that same situation. I want there to be visibility.”

Their journey underscores the importance of accessible science education and the potential of sparking a lifelong passion for discovery. For Postuma, a talking dog and a thoughtful physicist were the perfect guides into the quantum realm, proving that with the right approach, even the most complex scientific concepts can be made accessible and exciting.